Ecopedagogy is a discourse, a movement, and an approach to education that has emerged from leftist educators in Central and South America including Paulo Freire, Moacir Gadotti and Leonardo Boff that seeks to re-educate “planetary citizens” to care for, respect and take action for all life.

What is Ecopedagogy?

Ecopedagogy is a discourse, a movement, and an approach to education that has emerged from leftist educators in Central and South America including Paulo Freire, Moacir Gadotti and Leonardo Boff that seeks to re-educate “planetary citizens” to care for, respect and take action for all life. How can we, as citizens of the planet, participate in the creation of a world that we want instead of simply observing those who are profiting off of extraction and exploitation create our world for us? What does an education look like that can encourage people to face what is happening, take responsibility for ourselves and work to create healthy, vibrant resilient communities that serve everyone, no one excluded. What kind of education is really relevant today, given our current social and ecological crisis? How is traditional environmental education not relevant? These are some of the questions that are asked by ecopedagogy, which it attempts respond to.

Workshop:

Ecopedagogy for educators and activists: In this highly interactive workshop we will explore key concepts including Post Issue Activism, Planetary Citizenship, Arts Education/ Arts Activism, Care, Ecological Justice, Praxis, Vision and Strategy, Sustainability and Resiliency. We will also provide tools for designing a relevant curriculum, problemetizing environmental education, and integrating ecological justice, love, care, respect, and creativity into every aspect of your classroom or training.

Okay, but what is it really?

As a movement and an approach to education, Ecopedagogy is alive; it is open and fluid to be defined by its practitioners who engage critically with it. In this way it remains continuously relevant. There are however, some basic principles outlined in the Ecopedagogy Charter, which have been elaborated and interpreted by subsequent works. Some of these principles include;

- Popular Education: Ecopedagogy is an extension of Paulo Freire’s seminal work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Many of the concepts of power and oppression are expanded to include the non-human world as oppressed as well. As a heir of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Ecopedagogy is grounded in popular education in which power is shared, participatory dialogue is the key methodology, learning leads to action, and learning starts from and responds to the learner’s lived experiences.

- Post-Issue activism: Issues of social and economic justice, democracy and ecologal integrity intersect and are interdependent. Ultimately none of them are possible without all of them intact. Educators can choose which ever issue their learners are most personally connected with however as an “entry point” or location to start from to then move towards an integrated understanding of the others.

- Planetary Citizenship: Our lived reality is becoming globalized, we should globalize our sense of community, responsibilities and our commitments as well.

- Art Education: Ecopedagogy encourages people to develop the capacity to feel, intuit, imagine, create, relate, and express themselves. In this way we move from object to subject, able to participate in articulating and creating the world we want. This implies that the multiple languages/ intelligences of theatre, music, visual art, photography, dance etc. are fundamental to engage with as tools of expression and creation in the educational project.

- Care: Dis-care of each other and of the planet has contributed to our current planetary crisis. Care can “conjure the strength to search for peace in the midsts of conflict”, “rescue the dignity of the condemned” and “permit a revolution of tenderness to prioritize the social over the individual.” ~Leonardo Boff, “Saber Cuidar”.

A note on the history of Ecopedagogy: Paulo Freire, Moacir Gadotti and Francisco Gutierrez were having lunch in Sao Paulo Brazil one day in the late 1990’s and came up with the word and basic concept of Ecopedagogy. Along with organizing the International Meeting, “The Earth Charter in an Educational Perspective”, all three of them then set out to write books on the subject. Gadotti wrote “Pedagogy of the Earth” Gutierrez wrote “Ecopedagogy and Planetary Citizenship” Freire however passed before he was able to write another book. Since then Leonardo Boff of the Liberation Theology movement and multiple others have joined them in Latin America to form what has become an Ecopedagogy movement, based out of the Paulo Freire Institute in Brazil. There are currently 3 Ecopedagogy centers in Brazil, one in Costa Rica and multiple articles, practices and resources in Spanish and Portuguese on the internet. Recently Richard Kahn published the first book in English on Ecopedagogy: Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary Crisis: The Ecopedagogy Movement (Peter Lang, Jan. 2010)

AN ARTICLE"Unless and until we have assigned meaning to our experience of our place, the earth, our bodies, the world as holy- we cast meaning outside of ourselves to “the closest and shiniest thing” Modern reference point for meaning and identity is consistently placed onto external authority, the media and fads, instead of from within. We need fellowship and communion- we are given a grafted version of “common experience”- but this does not offer relationship with the earth or communities." ~ Frank MacEowen

Place-based learning in teaching and teacher education November 1, 2016

Posted by Editor21C in Directions in Education, Engaging Learning Environments, Primary Education, Secondary Education, Social Ecology, Teacher, Adult and Higher Education.Tags: ecopedagogy, environmental education, social ecology, teacher education, technology and education

trackback

Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn. (Benjamin Franklin)

Place-based education is part of the broader ecopedagogical movement in education that connects learners with and immerses them in their natural locale (Kahn, 2010; McInterney & Smith, 2011). These connections are understood to be best developed authentically, over time and with gentle positive immersions in the natural world (Sobel, 2014). This ‘in-place’ approach is also argued to be a built on process, connecting students with their local community through repeated immersions in order to develop a sense of agency with and planetary citizenship for the lived-in world (Hung, 2014; Sobel, 2014). Place-based education therefore plays an important role for engaging students with notions of ‘place’, identity’ and ‘community’ and, for developing local-global connectivity and citizenship in these times of significant environmental challenge (McInerney, Smyth & Down, 2011; Misiaszek, 2016).

Place-Based learning is also a particularly useful and energising approach in light of today’s Australian Curriculum reform and eco-pedagogy paradigm shift (ACARA, 2012). With the inclusion of an eco-pedagogical approach in curriculum and syllabus documents, immersing children in the natural world, it moves from an optional fringe pedagogy to mainstream when implementing the Humanities and Social Studies Learning Areas in the Australian Curriculum and the NSW BOSTES History and Geography Syllabuses for the Australian Curriculum (ACARA, 2012; NSW BOSTES, 2012). However, if we are to implement this approach in a school context for deep learning about the world around us, educators need to leave indoor classrooms so that students can be immersed in the natural world ‘up close’ (Kahn, 2010; Knight 2016; Liefländer et al, 2015).

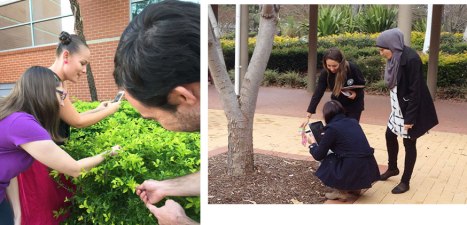

One of the core aspects in the Human Society and Its Environment subject in the Master of Teaching at Western Sydney University provides future teachers with a sense place by involving them in place-based activities within their local university environment. These strategies provide future teachers with a starting point for understanding hands-on, nature-based enquiry and provide model lessons for implementing positive immersion nature based explorations in their future primary Geography and History teaching contexts.

Many of these place-based tasks are supported by using technology in the learning experience and in the creation of learning objects back in the classroom thus making technology an invisible tool in the learning rather than a tokenistic add on (Hunter, 2015). One of the popular choices amongst the selection of activities is the nature audit. Vertical or horizontal metres are measured out and using a mobile device, photos of the components within the metre space are taken. Students then audit the collected data, categorising the manmade and natural objects, the interaction between the objects and the dominance of, or integration between these components (Fig. 1). The photos are then generated into a ‘Zoom’ slide show with a sustainability theme.

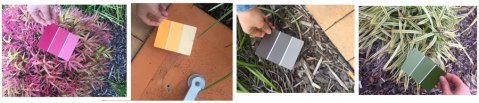

Kinaesthetic experiences are also popular with our preservice teachers such as matching paint colour swatches with colours from the natural and man-made local environment (Fig. 2). Students then ‘colour-map’ their environment, collecting data on colour dominances and tonal preferences. These data mapping activities are connected with earlier work in using Google maps, geo-mapping and geocaching for learning about local and global communities with school aged students. Conversations and ‘fat questions’ are raised about the dominant colours in our children’s school and in their wider communities. Other kinaesthetic activities involve recording natural and man-made sounds in their environment, which instigates interesting discussions about the impact of sound and the ‘white noise’ in children’s seemingly ‘always on’ world.

Figure 2: Colour in my world task

The strategies described here are but a sample of the place-based inquiries that our preservice teachers take part in but are ones that demonstrate the opportunities for rich discussion that these activities generate in terms of implementing place-based education with primary aged students. Moreover, the significant positive in task engagement that transpires when groups of preservice teachers work collaboratively in and about the natural world reinforces the different ways of knowing and learning that the outdoors offer all ages. As facilitators of these activities our team always looks forward to working with our groups as we share a common passion for supporting our future teachers in developing students’ connections with nature and develop pro-environmental agents of change (Liefländer et al, 2015).

So children can thrive and grow strong in challenging times ahead, let us engage them in nature, ethical conversations, and the building of caring and peaceful communities, in their schools and beyond. Winograd, K. (2016, p 266)

References:

Australian Institute for Teaching and Leadership (2016). Australian Professional Standards of Teachers, Author, Sydney.

Hung, R. (2014). In Search of ecopedagogy: Emplacing Nature in the lLght of Proust and Thoreau. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(13), 1387-1401.

Hunter, J. (2015). Technology Integration and High Possibility Classrooms: Building from TPack,

Routledge, New York and London.

Kahn, R. (2010). Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy and Planetary Crisis: The Ecopedagogy

Movement. New York: Peter Lang.

Liefländer, A., Fröhlich, G., Bogner, F., & Schultz, P. (2015). Promoting Connectedness with

Nature through Environmental Education, Environmental Education Research, 19(3), 370-384.

McInerney, P., Smyth, J., and Down, B. (2011). Coming to a Place Near You? The Politics and

Possibilities of a Critical Pedagogy of Place-Based Education, Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1), pp 3-16.

Misiaszek, G. W. (2016). Ecopedagogy and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization:

Essential Connections between Environmental and Global Citizenship Education to Save the Planet. International Review of Education, 62(5), pp 587-607.

Sobel, D. (2014). Place based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Green

Living: A Practical Journal for Mindful Living, 19(1), 27-30.

Winograd, K. (2016). Education in Times of Environmental Crisis: Teaching Students to be Agents of Change, Routledge, New York and London.

Dr Katherine Bates is a sessional academic in the School of Education at Western Sydney University, Australia. She currently lectures in Human Society and Its Environment at Western Sydney University and also in Literacy and Numeracy in Secondary Schooling at the University of Wollongong. She has had extensive experience as a classroom teacher across ES1-S4, EAL/D and literacy support, as well as senior leadership roles in curriculum and assessment with the Department of Education and Sydney Catholic Education.

No comments:

Post a Comment